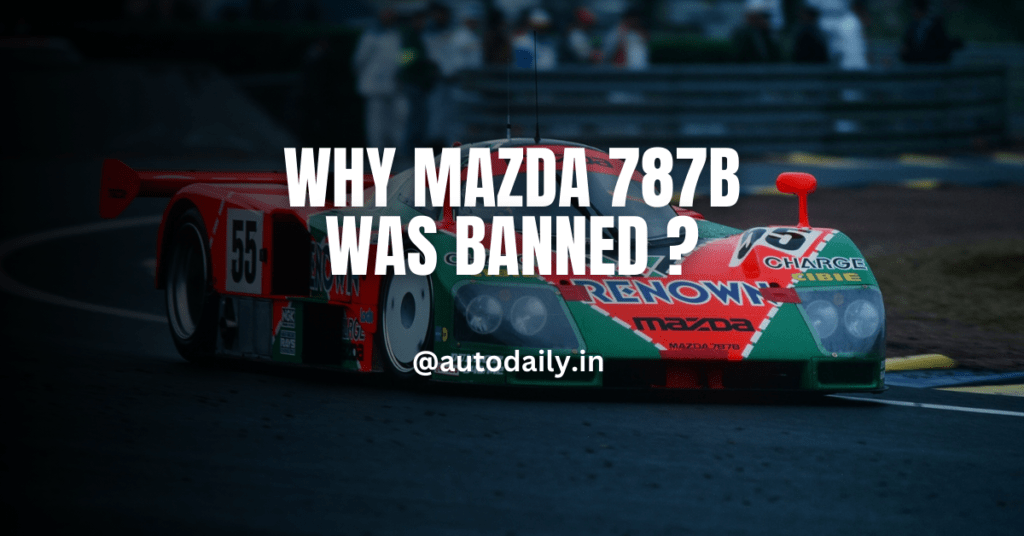

Why Mazda 787B was banned?

On a Sunday in June 1991, an entire country is silently watching TV. You see, history is about to be defined. Their hearts are full of pride, the Mazda peak, their hands clenched, eyes wide open. The 787B, on this day, during the 59th running of the 24 Hours of Le Mans, didn’t just finish first; every single channel in Japan broadcasts the same message. An entire nation’s ears are perked to the broadcast for the first time in their lives. Japan is winning, winning a fight thought to be unwinnable – the most grueling battle of the world’s nations, fought not with tanks and bombs but with petrol, tires, clenched teeth, and pure guts.

This is the story of the Mazda 787B.

This isn’t a story about winners, though. This is a story about losers that won. You see, the team at Mazda shouldn’t have actually won. They kind of never did. Let me set the stage. Back in the 1960s, Mazda had a new engine that they were very proud of – the rotary engine designed by Felix Wankel. This was a new, revolutionary way of exploding fuel. It was lightweight, simple, and compact. But, you see, Mazda was kind of the only ones that really believed in it. In their first touring car race, they didn’t even get on the podium, and that pretty much was Mazda’s racing luck.

Sure, they dreamed of winning Le Mans, but they were never really competitive. They did have a promising race car, the MC74, which, of course, broke down and never even finished the race. The RX-7 Le Mans car didn’t even qualify. Then, in 1984, by some miracle, they won a race in a car designed by Lola called the T616. Of course, this isn’t all that important because this is a slower class, but hey, at least for once, the rotary engine won. But then it was quickly back to failure with the 757, the 767, the 767B. Every year that Mazda entered the race, they were crushed by the competition.

The Rule-Breaking Marvel

But in 1990, they had come out with a new, incredible race car – the 787. Gone was the little two-rotor 13B, and in its place was the massive four-rotor R26B. And then, on a cold morning in 1990, the drivers left the line, and none of the 787s even finished. One had a little bit of engine trouble, and the other one, well, it just caught on fire and gave up. For decades, the rotary engine had been giving its all, but by the end of the 1990 racing season, there wasn’t much hope for it. On the horizon were rule changes that pretty much doomed it. In a few years, the rotary engine would be outlawed completely.

Look, for those of you that don’t know racing, there are three things that matter on a race track: the car, the driver, and the rules. You see, cars in the 1980s were getting a bit too fast, so the rules started to change.

The Changed Rules

The FIA, the organization in charge of Le Mans, wanted everyone to start adhering to Formula One standards. This meant that they were about to abandon all the cool, crazy experimental engines of the ’80s in favor of standard 3.5-liter engines. And these new rules were going to go into effect in the 1992 season.

You might have heard an old wives’ tale suggesting that officials outlawed the 787B because it was too loud or too fast. And yes, it was indeed very loud – track officials even warned spectators to cover their ears because of its volume. However, the truth is more humbling. It was outlawed due to some provisions in a rather mundane rulebook. So Mazda knew that in 1991, this was their last chance to prove that the rotary engine was a viable racing platform. So with that in mind, they went back to the drawing board. They pushed the 787 into the shop and got to work.

Challenges in Chrome and Carbon Fiber

What rolled out of that shop was nothing short of a technological marvel. Seriously, there was nothing like the 787B before. Designed by Nigel Stroud, a man who worked on the Porsche 956 and cut his teeth in Formula One, Stroud’s new 787B was lighter. He had convinced Mazdaspeed to spend the money and get a full carbon fiber monocoque with a body aerodynamically formed in a wind tunnel designed to maximize top speed on the Mulsanne Straight. It had carbon brakes, which was a revolution at the time, and most importantly, they had totally revised the four-rotor R26B engine.

Body Changes

This new version had ceramic apex seals, three spark plugs per rotor, and an insane and revolutionary continuously variable intake system that essentially made the car able to stay in its power band the entire time. Think of VTEC on steroids. This meant that the car was able to produce nearly 900 horsepower almost instantly and was incredibly efficient at it. And then Mazda went and detuned it to 700 horsepower to make it even more efficient and more reliable because this is endurance racing, and reliable and efficient are more important than speed.

I know, generations later after dealing with the RX-7s and the RX-8s of the past, it’s kind of hard to think about. But in 1991, Mazda had the most reliable, efficient engine in the race, and it was a rotary. Sure, insert your apex seal jokes here, but like everything is different on a race track when you push a car for that long to its very limits. All stereotypes fall by the wayside. The car was so efficient and reliable that they based their almost whole strategy of racing around it. In training, instead of the drivers trying to get the best lap times, they raced to see who could use the least amount of fuel.

Team Mazda and Drivers

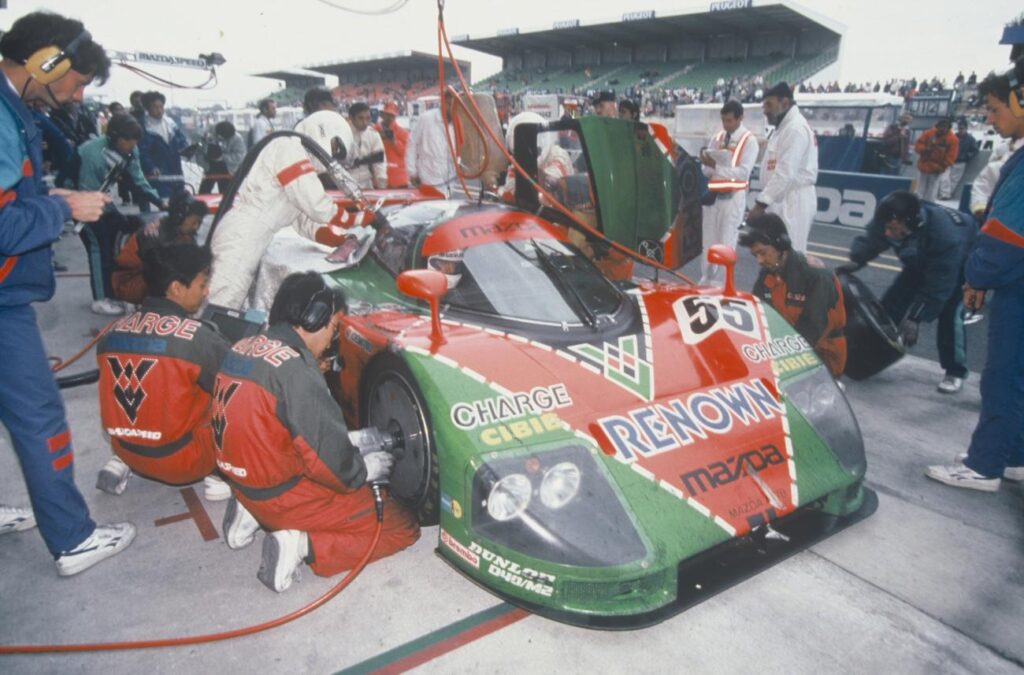

Wrapped in the now iconic orange and green renowned livery, the 787B was like nothing else, with its high-revving engine, with its insane torque curve and wild aerodynamics tuned for the straights. All that was left for Mazdaspeed was to find drivers that could actually tame this angry beast, to go the distance in a car that was constantly trying to kill them. Mazda needed the absolute best. What they got was a Formula 3 driver, a prisoner, and a man who doctors said could never race again.

Mazda’s team was French but was spearheaded by a Belgian man named Jackie Ickx. The drivers were from everywhere, including Belgium, Sweden, Ireland, and Japan. There were two teams of 787Bs in that 1991 race, but today we’re just gonna talk about the winners: Belgium’s Bertrand Garcia, Germany’s Volker Weidler, and hailing from the UK, the madman himself, Johnny Herbert.

Bertrand started the season in prison, thanks to an assault on a cab driver. Yeah, the dude sprayed a cab driver with CS gas over some road rage, spent a few months in prison, and then went racing. Volker had driven the Porsche 962C in Le Mans previously but had very few wins under his belt. Johnny Herbert was a Formula racing veteran who had an absolutely horrific accident in 1988 when his Formula car slammed into a barrier, nearly severing one of his feet and severely damaging the other.

Bertrand Made History

Doctors had to work on him constantly, and they told him that his racing career was over. However, in 1989, he found himself back behind the wheel. He found it really difficult to press the brake pedal, and he couldn’t run for the Le Mans start, but he could win. Together, this team of wacky individuals – a prisoner, a rookie, and a man with a limp – set out on June 22, 1991, to rewrite history.

It’s three o’clock in France; the 24 Hours of Le Mans has just begun. The number 55 Mazda 787B is all the way back in 19th place, despite qualifying for a better spot. Due to rule changes and the FIA’s aspiration to align everything with Formula 1, they reserved the top 10 spots for those who adhered to the rules, and the 787B deviated from these regulations. Consequently, it began the race from a much farther position. Additionally, the penalty for non-compliance with these regulations involved adding 200 kilograms of ballast to the car, equivalent to approximately 440 pounds for those using the hamburger system.

The ballast didn’t really make that big of a difference. As the race started, the Mercedes team with all the extra ballast, piloted by none other than Michael Schumacher himself, quickly pulled ahead of the Peugeot team that did not have the ballast. The raw power and skill of the Mercedes teams meant they were favored to win the race. 400 pounds be damned. Against all odds, though, right behind the Mercedes powerhouse was a team that no one expected to see – the number 55 Mazda 787B, which, as night fell, had climbed up to fourth place.

The Unbelievable Quest

You see, no one, not even Mazda themselves, really believed that the 787B was going to be competitive. So when it came time to hand out that extra ballast, Jackie Ickx was actually able to convince officials that the Mazda 787B was powered by a small displacement naturally aspirated engine. And no other team thought to question it because no one really cared. They thought the Mazda team was just kind of cute. So the 787B left the line with a lightweight 830 kilograms, ready to hunt down and overtake those heavy 1000-kilogram Mercedes Benzes and Porsches.

The big manufacturers’ lack of respect for the Mazda team eventually ended up being their downfall. As night fell upon that track in France, the Mercedes team could not shake the Mazda. Then, one by one, the Mercedes all kind of fell apart. The number 31 had gearbox issues; number 32 ran into some debris, and suddenly, the underdog Mazda team was in second place. In first was the number one team Mercedes, and the team at Mazdaspeed could smell blood in the water.

As the race drags on, Jackie Ickx notices that the number one Mercedes is taking a slower pace. He reasons that they’re trying to conserve fuel. You see, the extra weight and larger engine were starting to take their toll. And even though Jackie is usually very cautious, he tells the team to push it. And then, in the 11th hour, or sometime around the 22nd hour, I guess, pushed to its limits by the angry pack of bees behind it, nipping at its heels, the Mercedes-Benz begins to overheat and has to pit in, letting the underdog Mazda 787B finally take the lead.

All Struggle was Worth it!

Throughout the course of this race, the little loser team from Japan that nobody thought was going to be in the top 10 was suddenly number one. All of Japanese TV was tuned into this race at this point, as Japan was leading the world’s most prestigious endurance race. A ragtag group of ruffians driving a strange car with a stranger engine was ahead of auto industry titans. Mercedes, Jaguar, Porsche, were all sniffing the exhaust fumes of a Mazda. To stay ahead, they had Johnny Herbert do a double stint at the finish, you know, the guy with the broken feet.

By the end of the race, he had no water; he was dehydrated as hell. His ankle was killing him; the pain was so bad he almost passed out. On top of that, he had stomach problems; he was nauseous, he was anxious, he was exhausted. He was stretched so thin you could see through him. But he kept pace. The wild rotary engine had finally proven itself in its dying breath of the Le Mans series as a giant middle finger to the officials that outlawed it. The Wankel rotary engine pushed past everyone, and its horrifying scream echoed through the valleys of France as it finally crossed the checkered line – first place to Team Mazda.

Winning Moment

As Herbert finally passed under the checkered flag in the 787B, the newly crowned champion was in pretty rough shape. He had to be dragged out of the car and put into an ambulance. Herbert didn’t even get to stand on the podium. But that’s the beauty of endurance racing. It’s both a test of man and machine. In 1991, Mazda, and by extension, all of Japan, aced the test, becoming the first Japanese team to win the 24 Hours of Le Mans. It was the culmination of efforts from engineers, drivers, and mechanics, a result of persistent hard work and numerous setbacks, resulting in pure gold. And that is the story of how Mazda and Japan finally won the 24 Hours of Le Mans.

Join Us : WhatsApp Channel

FAQ

The Mazda 787B is a Group C sports prototype racing car developed by Japanese automaker Mazda. It competed in the World Sportscar Championship, All Japan Sports Prototype Championship, and the 24 Hours of Le Mans from 1990 to 1991.

The 787B is iconic because it was powered by a rotary engine (Mazda’s R26B). It remains the only car with a non-reciprocating engine design to win the 24 Hours of Le Mans.

While lacking the single-lap pace of rivals like Mercedes-Benz and Porsche, the 787B’s reliability allowed it to contend for championships. It eventually secured victory at the 1991 Le Mans with drivers Johnny Herbert, Volker Weidler, and Bertrand Gachot.

The rotary engine was not directly banned. However, changes in regulations and the move to 3.5L engines led to the demise of the rotary-powered cars.

The 787B’s Le Mans win in 1991 marked the first victory by a Japanese manufacturer and remains the only non-reciprocating engine victory in the race’s history.

While lacking outright speed, the 787B’s reliability allowed it to challenge European powerhouses. It proved that consistent performance mattered.

The 787B evolved from the earlier 767 and 767B designs. Nigel Stroud led the design, focusing on improving the intake system of the rotary engine.

The name indicated a two-step improvement over the 767. It was chosen over “777” due to pronunciation difficulties in Japanese.

The 787B’s Le Mans victory is etched in history. It showcased Mazda’s engineering prowess and the potential of unconventional engine designs.

While unlikely, the 787B’s legacy continues to inspire automotive enthusiasts and racer worldwide.